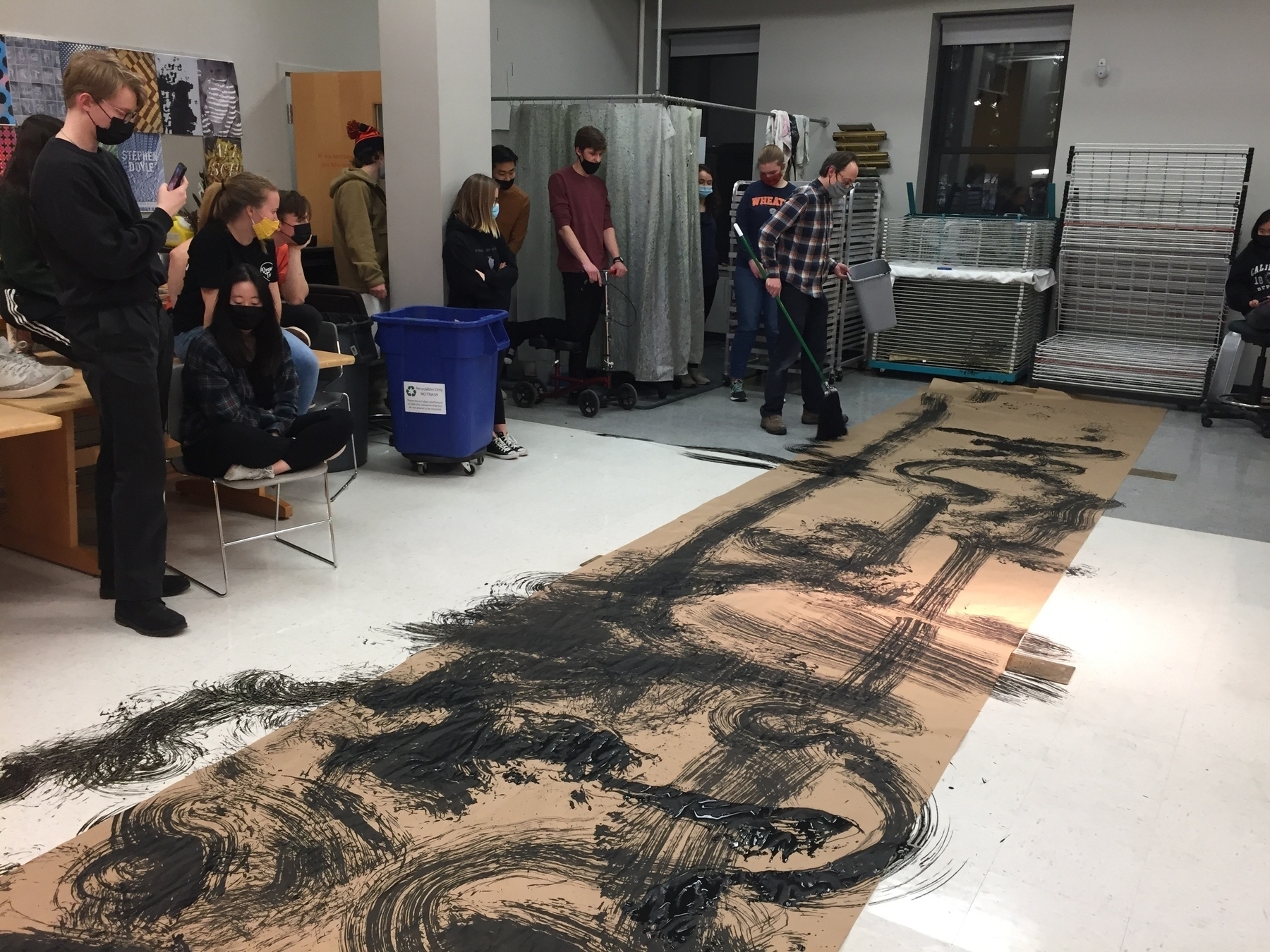

Station #8, Asemic Writing: All the pieces in this exhibition resist our standard operating procedure when encountering writing, which is to decode it for information and move on without another look. That kind of functional view of writing is faced with its sharpest challenge, though, by “asemic” writing, meaning writing that has no semantic referents. Asemic writing comes in a variety of forms, from lines and squiggles that resemble, however faintly, familiar letter forms to complete alphabets for scripts that have no phonetic or logograph correspondents. (In other words, here are signs that don’t represent sounds or concepts.) Why, you might wonder, would an artist do this? There are surely as many answers to that question as there are asemic writers, but in many cases the answer surely involves a pure, uninhibited delight in the shapes of letters and characters and the design principles undergirding writing systems. In this way, asemic writers help us to regain a childish wonder at the curious markings that fill our books, flash out of our screens, sit on and in our flesh, and coat our buildings. And even without “content” of a traditional sort, asemic writing still often has connotations, that is to say, it triggers emotional and cultural associations. What do you see in the asemic scrolls in front you?

Station #9, Sky Scroll: This work has profound personal significance for the artist, which will be explained briefly here and at great length in the “Digging Deeper” section. But to appreciate where this work is coming from, we need to shift our attention from West to East, specifically to ancient China. Calligraphy was often regarded there as the highest art form, the skilled calligrapher’s brushstrokes being expressive in their own right. The Han-era Confucian scholar Yang Xiong memorably named writing the hua 畫, “painting or picture,” of the xin 心, heart or mind. The calligrapher’s scroll, normally read vertically, was a kind of self-portrait no matter the text.

That is what you see here. On one side, Professor Botts has rendered Frederick Lehman’s classic hymn, “The Love of God is Greater Far,” which imagines that even a team of scribes with ocean of ink and a scroll as wide as the sky would fail to account for God’s love. On the other side, he has written in Hebrew God’s response to Job from the whirlwind in white ink. These two texts serve to mark the complicated mixture of feelings created in the artist at the demolition of his childhood home and the discovery of an “unexpected scroll” in the form of a roll of old wallpaper in the attic of his late grandparents’ house. Professor Botts’s writing is not legible to us in a word-by-word fashion, but that’s not the point. He writes to bear out his xin, to channel his grief and gratitude, to reckon with losses, to rejoice in remembered blessings. On architectural tracing paper, we see a scroll thrown up in the sky. Perhaps we aren’t its primary readers.

Station 10: Hebrew Typewriter: For thousands of years and in numerous cultural contexts, artists have roamed the borderlands between poetry and visual art. In our modern context, we use categories like “concrete poetry” and “visual poetry” to describe modes of expression where the shape of the text, its visual effect, is of equal, if not greater, significance than the text itself. Indeed, some visual poets don’t write recognizable words at all; instead, their designs encourage us to think about letter forms—their physiques, cultural associations, and non-semantic functions (such as when we use letters as variables in mathematical equations). This station invites you to think about the visual potential of letter forms by using a machine that uses a script, or writing system, that is in all likelihood recognizable to you but still unfamiliar. Here is a Hebrew typewriter, generously donated to the Technotexts seminar by our friend Steven Bob, emeritus Rabbi of Congregation Etz Chaim in Lombard. Professor Botts has made left some sample visual poems and left them on the wall behind you. Make you own, or contribute to one that is in progress; when the work is complete hang it on the nails behind you. And don’t worry about covering someone else’s work, the display will be rotated daily.

Station #11, Pictograms: Many of the letters and characters in the world’s writing systems began as pictures of something, what linguists call “pictograms.” Our letter “A,” for example, likely began as a hieroglyph representing an ox in ancient Egypt before two processes took place, the image was abstracted, its shape pared down to three lines, and the symbol’s referent switched from a thing to a sound. As one observer has noted, all that’s left of the ox now is its horns. In the first making exercise of the Technotexts seminar, we ask students to make simple pictograms of their own that symbolize their memories, aspirations, losses, hopes, and delights. The larger sheets attempt to narrate a year or even a life pictographically. What stories do you see emerging here? What symbols would you choose to tell your story?