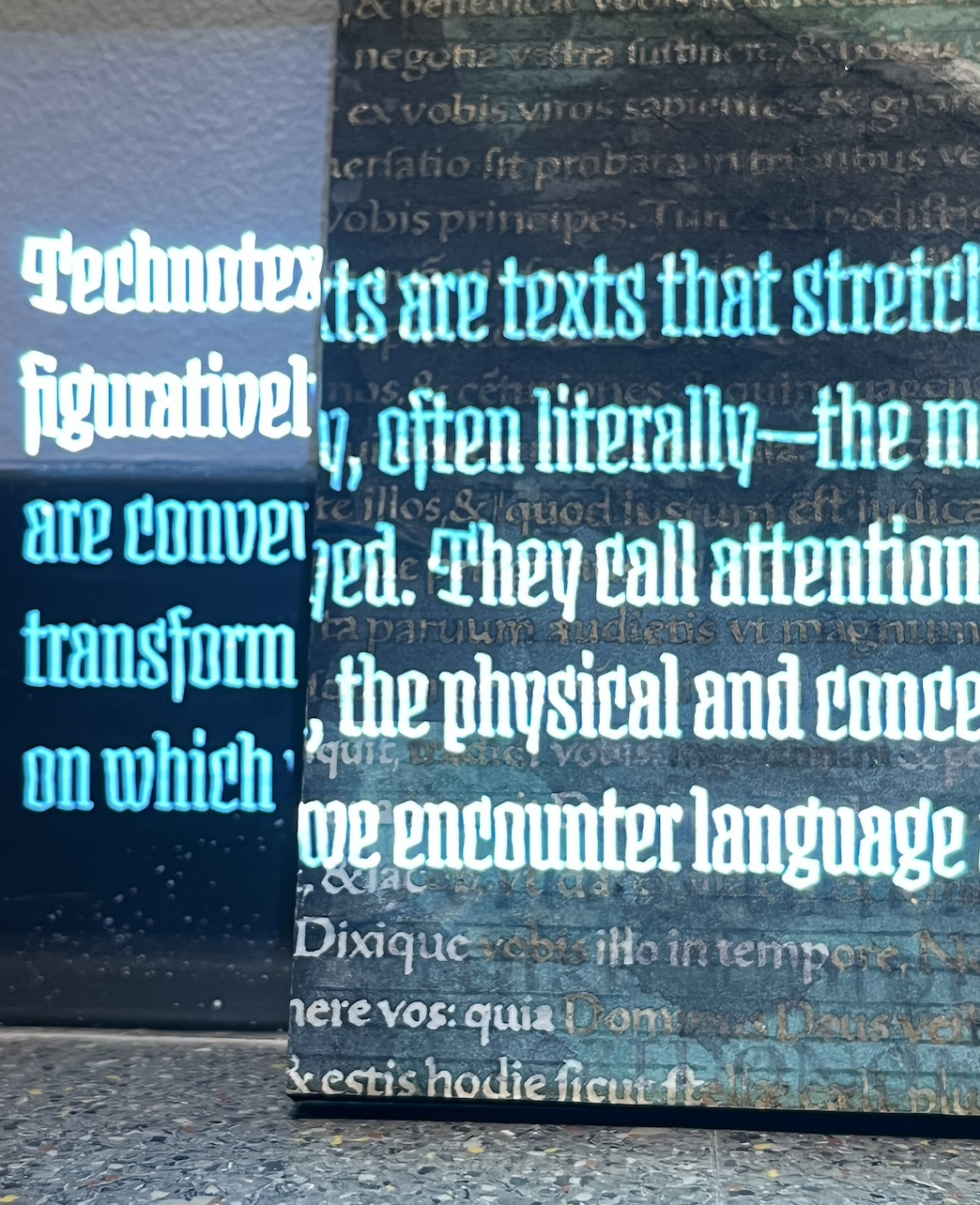

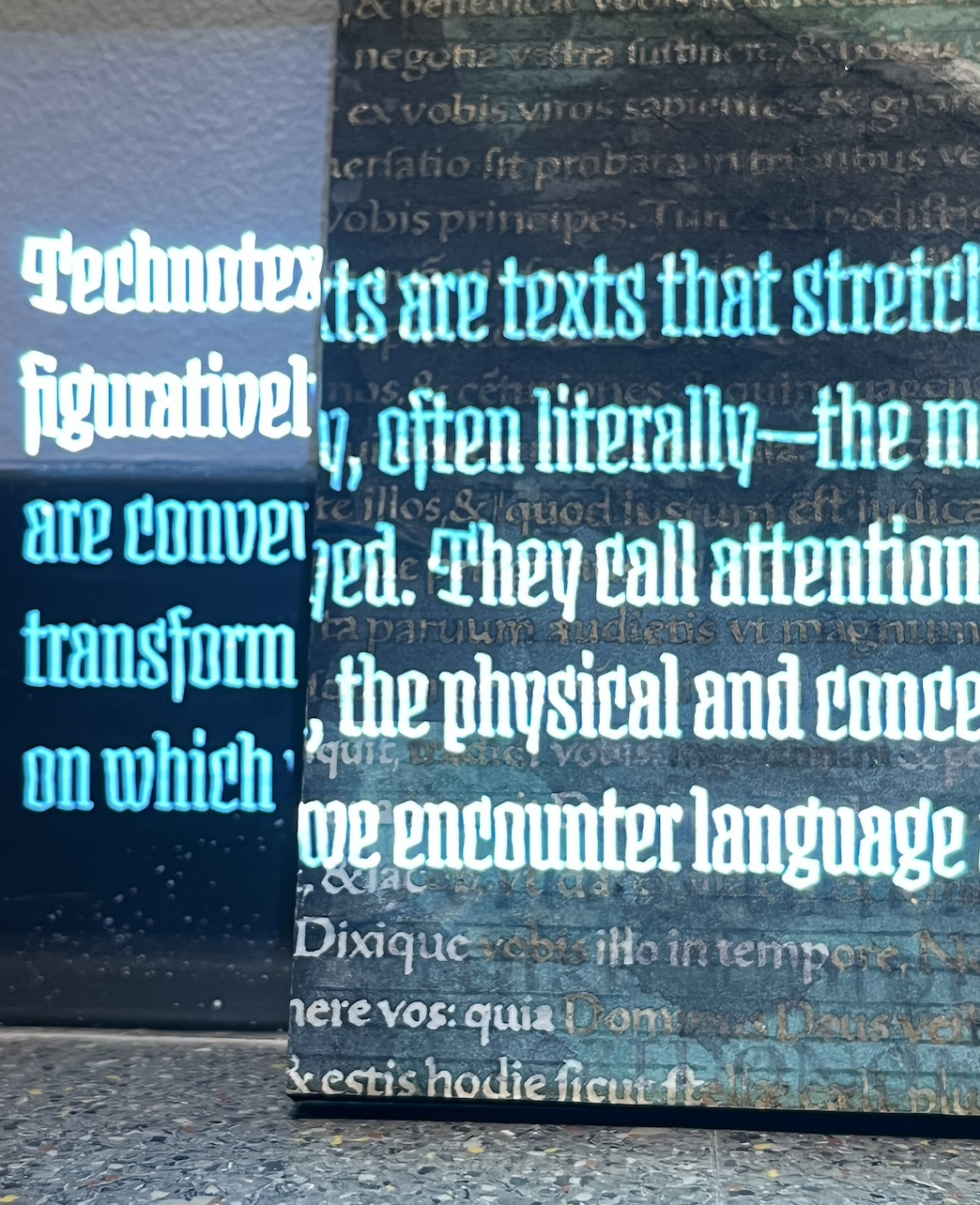

Words of Welcome:

What is a gallery? Many of us are taught, directly or indirectly, that a gallery is a space for fragile, expensive things best appreciated at a careful distance, in whispers, and with a raised eyebrow. You’ll have to check those assumptions at the door here. We invite you to step in to the work on display; look at it closely, consider what it’s made of, how the materials were used, and how it uses writing to accomplish goals other than or in addition to providing information. In some cases, you’ll be invited to handle the pieces themselves or early drafts, in others to contribute some markings yourself. In so many ways, the gallery functions here less as a showcase than an extension of our classroom, in which we study the reciprocal relationship between language and materiality by reading about media and making media, by using our minds and our hands. Welcome to the Technotexts seminar.

Station #1, Clay:

Writing begins with Mesopotamian mud. That’s what the archeological record shows us. Back in the fourth millennium BC, the ancient Sumerians began to take advantage of the abundant clay around them to keep track of livestock transactions. Gradually, the Sumerians realized that they could symbolize other things as well, and the first written system of communication, called cuneiform after the wedge-shaped instrument used to render it, was born. In this station, we invite you to explore the impressionable nature of clay. Press it. Erase it. Explore the effects of the instruments on the tabletop. Experience writing in its original medium.

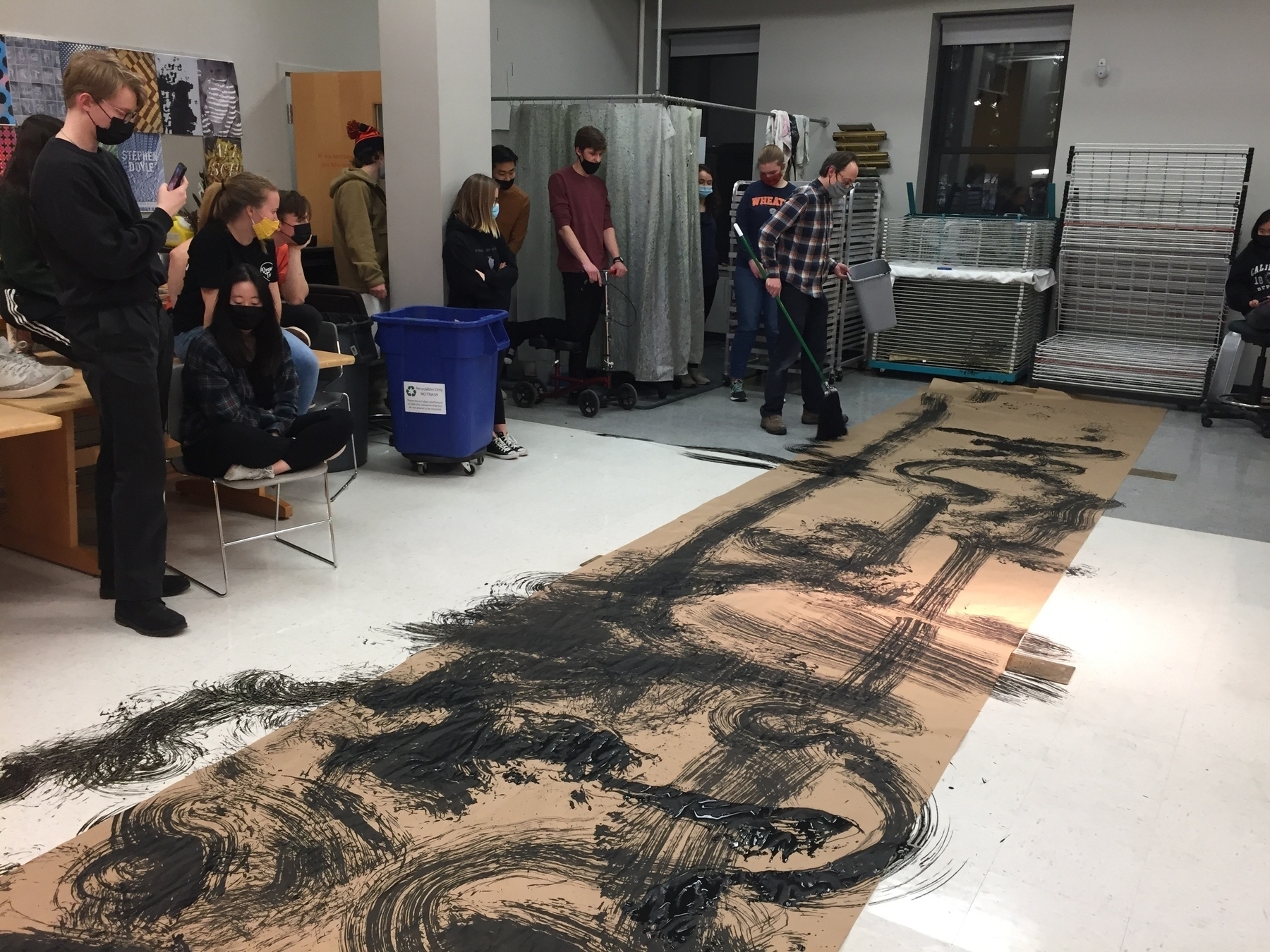

Station #2, Concrete Confessions:

What materials can you use to write? The historical answer is, in fact, almost anything! Down through the centuries, seemingly anything close at hand, and many things not easily acquired, have become the stuff of writing, including acorns, aluminum, alcohol, bamboo, birch bark, bitumen, bone, bread, bronze, copper, chalk, clay, dung, electrical wire, felt, feathers, fiberglass, flax, gold, grass, goat hair, graphite, gum, hemp, hides, iron, lemon juice, knives, linen, lead, leaves, mulberry, mercury, nitric acid, oil, ocher, papyrus, pottery, especially broken bits, plastic, quipu strings, rags, rice, resin, sandstone, silk, steel, soy, sunlight, terracotta, tortoise shells, ultraviolet rays, vinyl, wax, water, wheat, wood pulp, X-rays, egg yolks, and zinc, among countless other materials. In this case, Professor Botts is doing as the Romans did: he is writing in concrete, a process that required him to begin by “writing” in reverse in his mold so that the message would face the viewer correctly. Writing in the “artificial rock” that is concrete is far more permanent than our scratchings on paper. What words are worthy of such treatment?

Station #3, Letter Pillars:

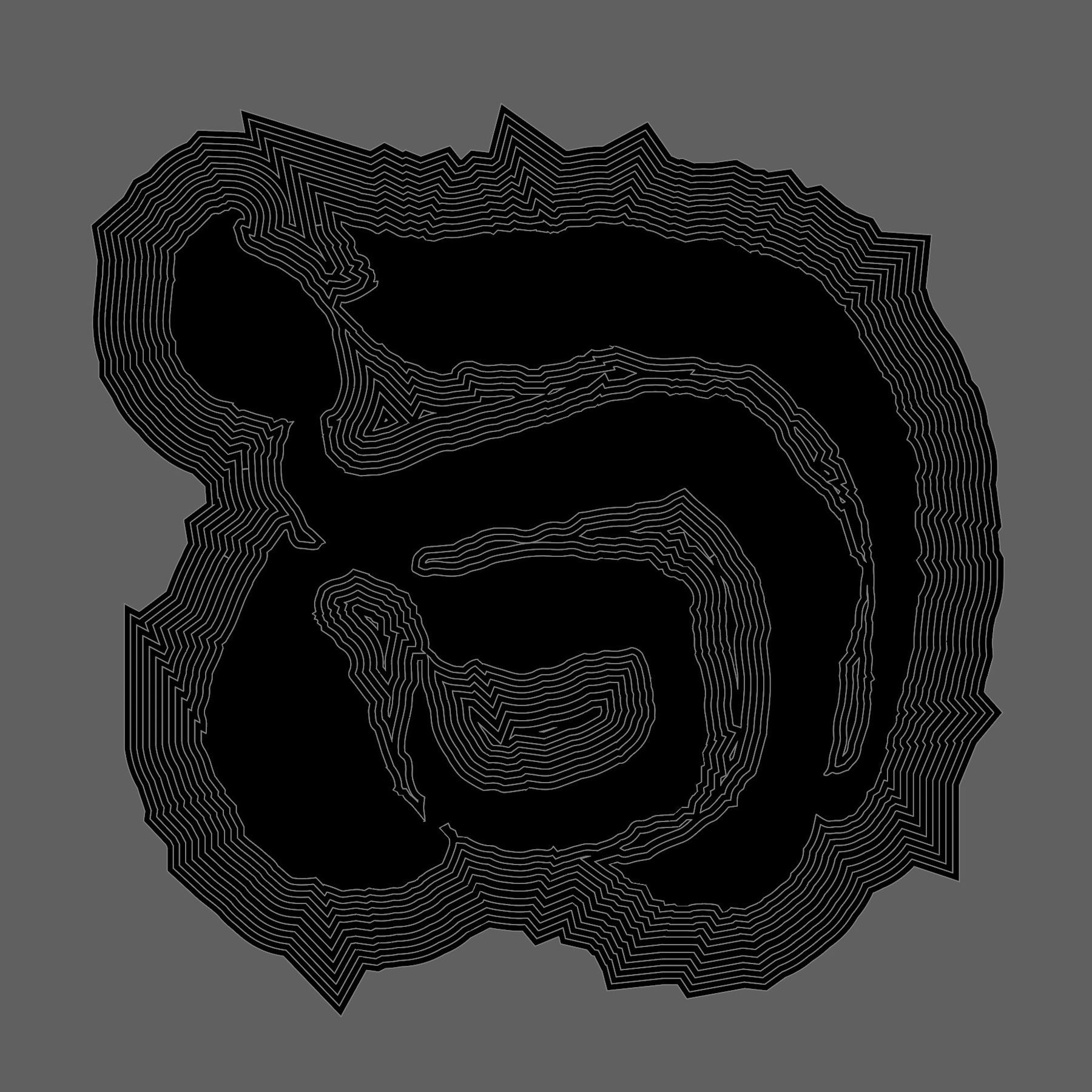

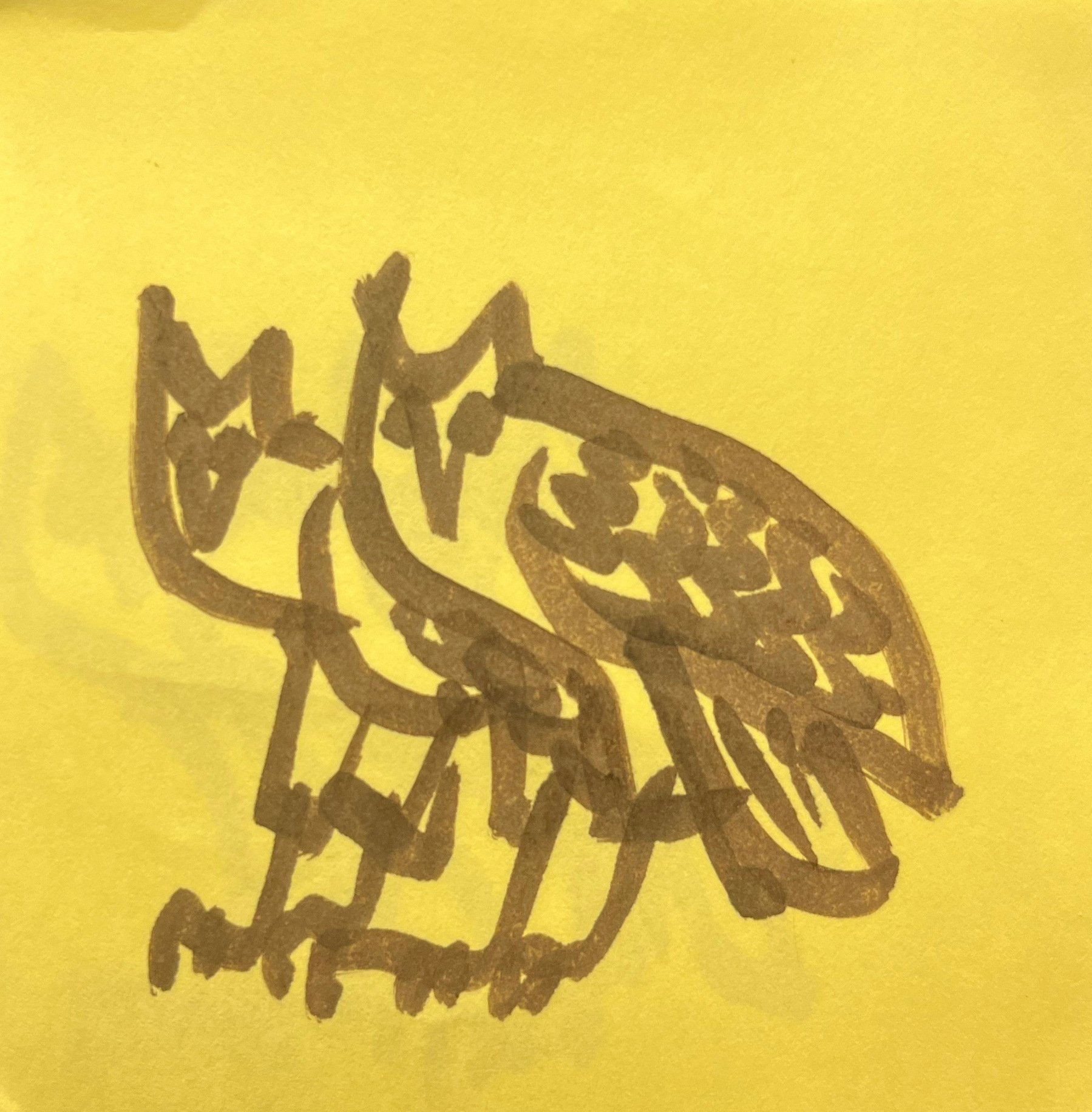

After becoming proficient hand-writers in elementary school, many of us come to take the shapes of letters for granted. In fact, we pride ourselves on looking right past them in order to recognize the things and concepts they symbolize. We render them transparent. Artists like Professor Botts invite us to look again. They defamiliarize letter forms so that we can once more SEE their loops, junctures, and jagged edges. In these pieces, Professor Botts resists our tendency to look down on letters. By adding a third dimension, laying characters on their sides, and stacking duplicates, he allows us to look at letter forms from multiple cultures from fresh angles.

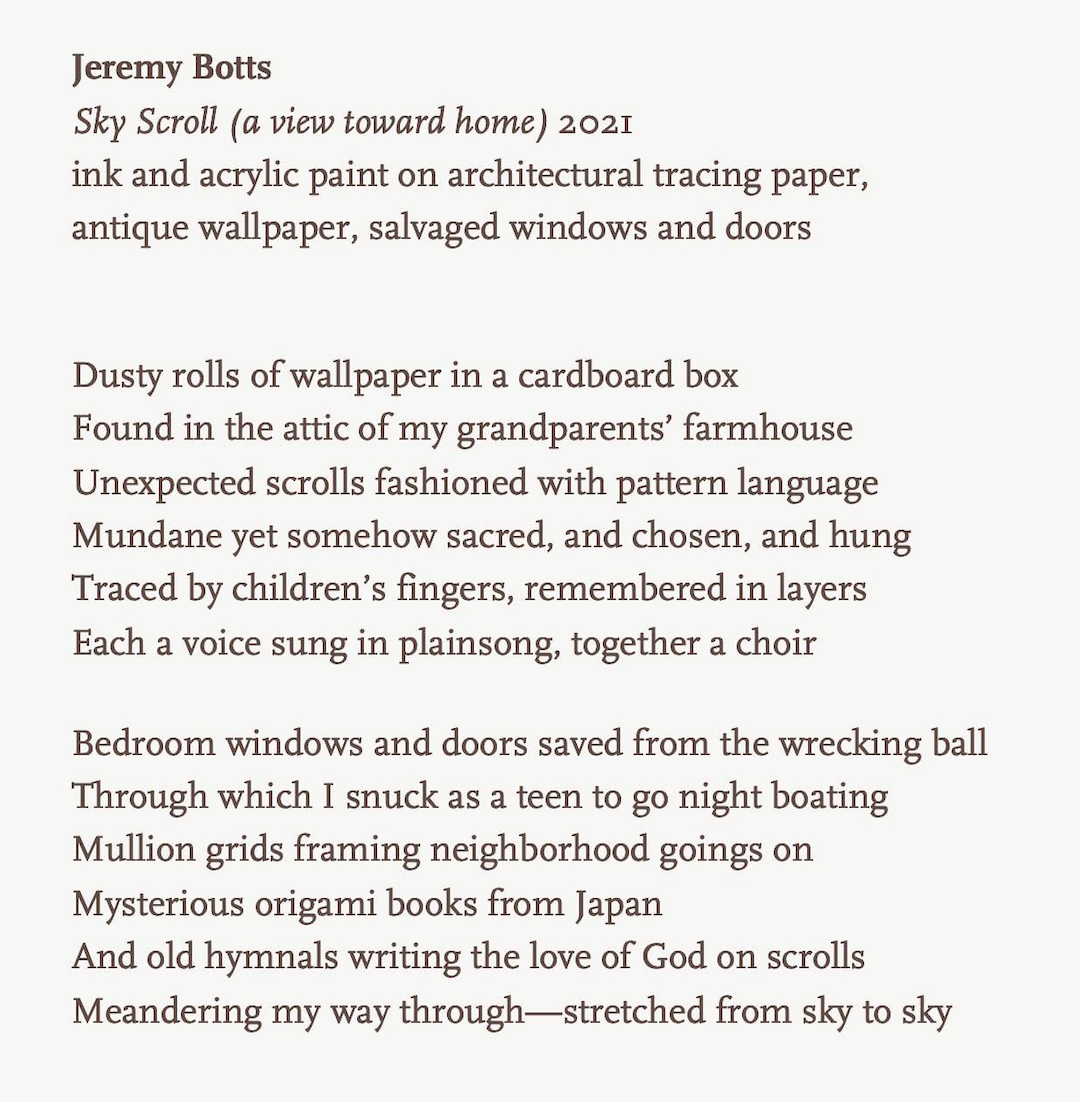

Station #4, Scripture Scroll:

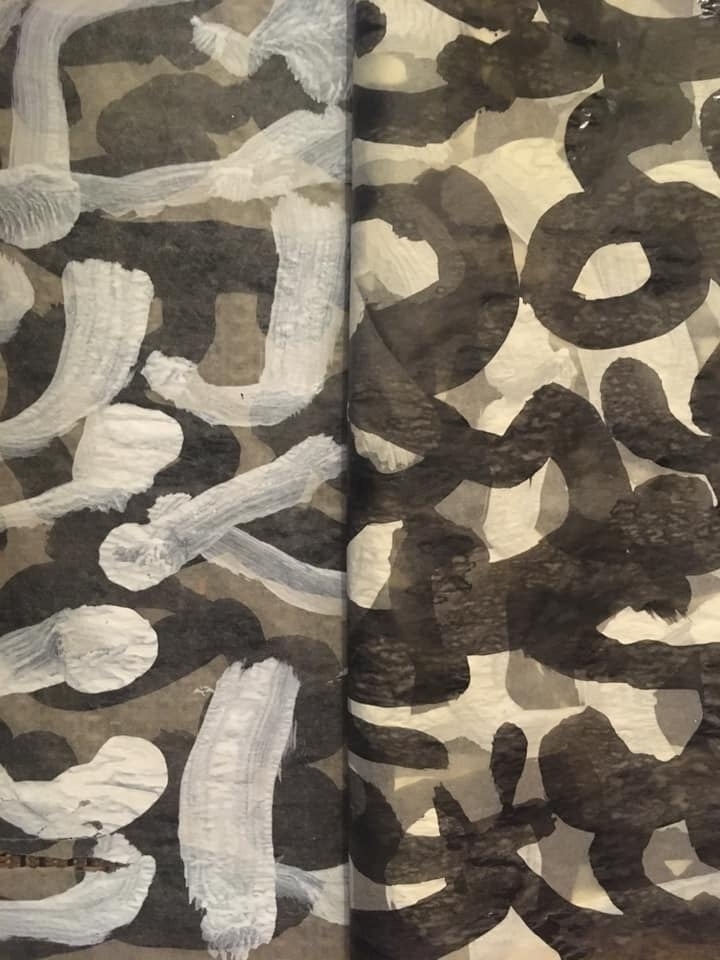

The Bible is a book of writings, a library, but it is also a book very much concerned about writing. In Genesis, we already find traces of writing, as in the “book” of Adam’s descendants listed in Chapter 5. But it isn’t until Exodus that we read directly of the act of writing. The first discussion, fittingly, concerns the Lord’s gift to Moses, in chapter 31, of “two tablets of stone written by the finger of God.” Moses, of course, destroys those tables, and then he is enlisted as God’s scribe in Chapter 34, again writing the Lord’s “Ten Words”—i.e. commandments—in stone. Professor Botts has written those words on this scroll using clear, water-resistant Latex, which he then revealed by coating the paper in tea. Between the lines of the Hebrew, the work lays a second text very much concerned with writing—the second chapter of 1st John—in which the apostle repeats the phrase “I am writing” eight times in the space of seven verses. Writing for John is a means of connection, of truth-telling, of reassurance, but above all, of love. In his composition, Professor Botts reminds us not only of these gifts of writing but also of the scribal tradition that bore these texts down through centuries prior to the advent of print.

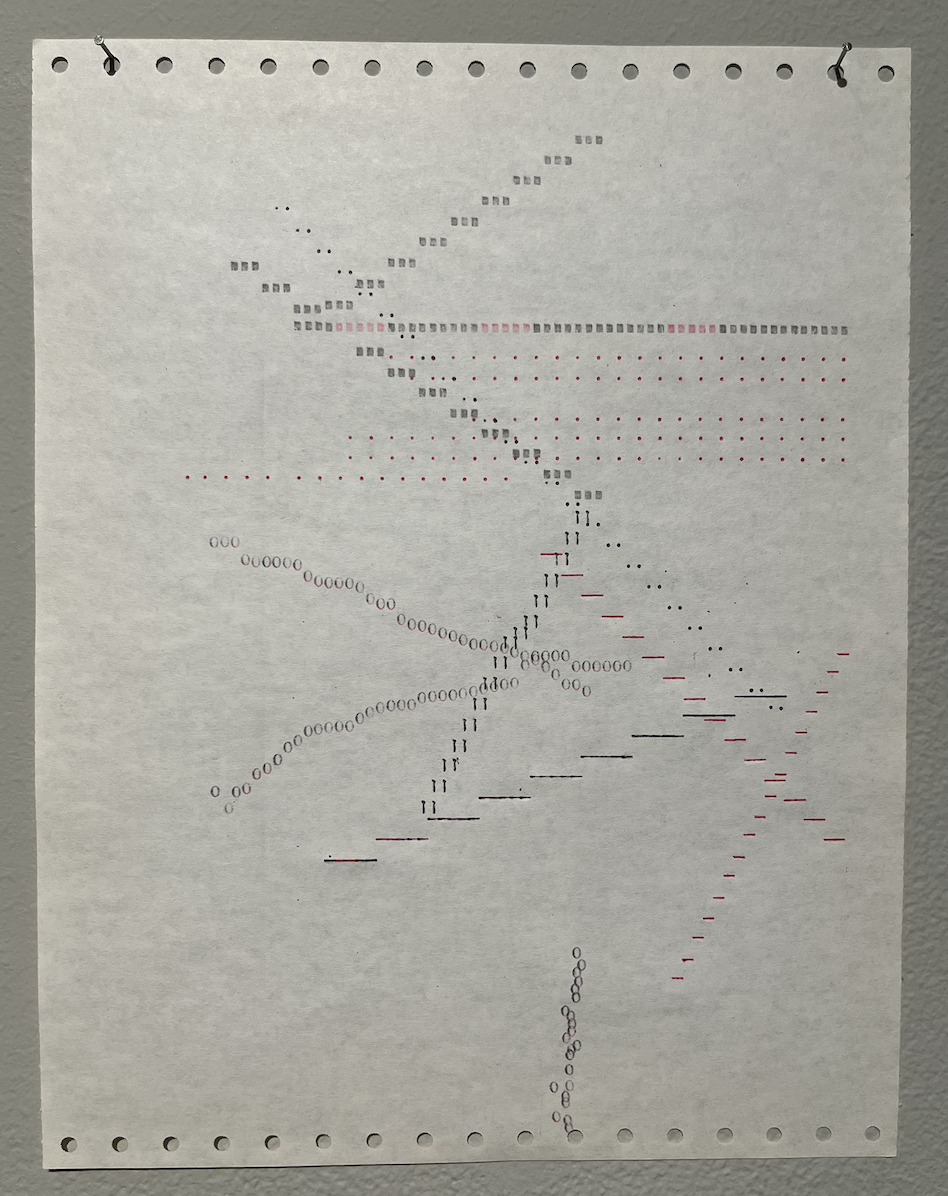

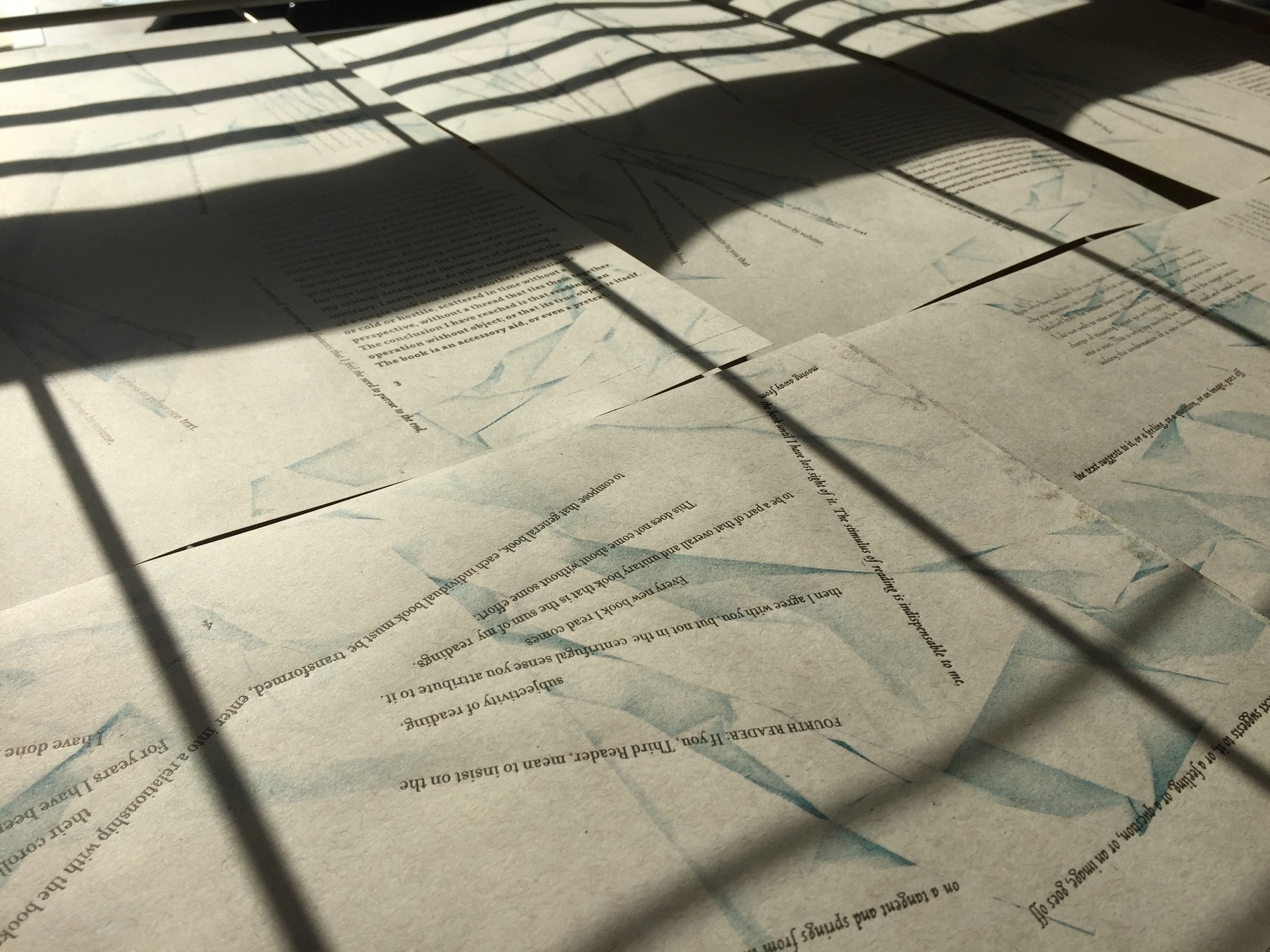

Station #5, Calvino Reader:

Italo Calvino’s 1979 novel If on a winter’s night a traveler is an elaborate exercise in metafiction, that is, fiction about the art of fiction. The story follows the efforts of a reader named “you” (the pronoun not the letter) whose attempt to read the novel If on a winter’s night a traveler leads you on various misadventures in the world of books. In the eleventh chapter, you wander into a library, where you find seven readers, each of whom reads in a distinctive fashion and longs for books that match that style. The chapter is, in other words, a study of reading strategies and desires. The pamphlet takes this Calvino madness several steps further. The designers have chosen a typeface for each reader and, using sliced up photopolymer plates, arranged the readers’ statements in patterns that embody their personalities. We invite you to read the pamphlet and to look for yourself. Which Calvino reader are you?

Station #6, All Eyes:

“The eyes of all look to You and You give them their food in its season. You open your hand’s expanse and give every living thing its delight.” That’s our translation of Psalm 145, verses 15 and 16, the jumping off point for the piece before you. The psalm’s imprint on the design is conspicuous in the lattice of eyes that you see repeated in the panels. But the psalm’s influence lies still deeper. Psalm 145 is an alphabetic acrostic, each of its verses beginning with a different letter of the Hebrew alphabet—“ayin” and “pey” in verses 15 and 16. The acrostics demonstrate that writing more than just a convenience for ancient Hebrew poets; they are playing with the alphabet in these poems, showcasing it, making it a principle of order and a test of artistic skill. The work engages with modern textual technologies—particularly the risograph and the lasercutter—in the same playful spirit, gathering texts and images that express students’ responses to the sacred, beginning with Psalm 145.

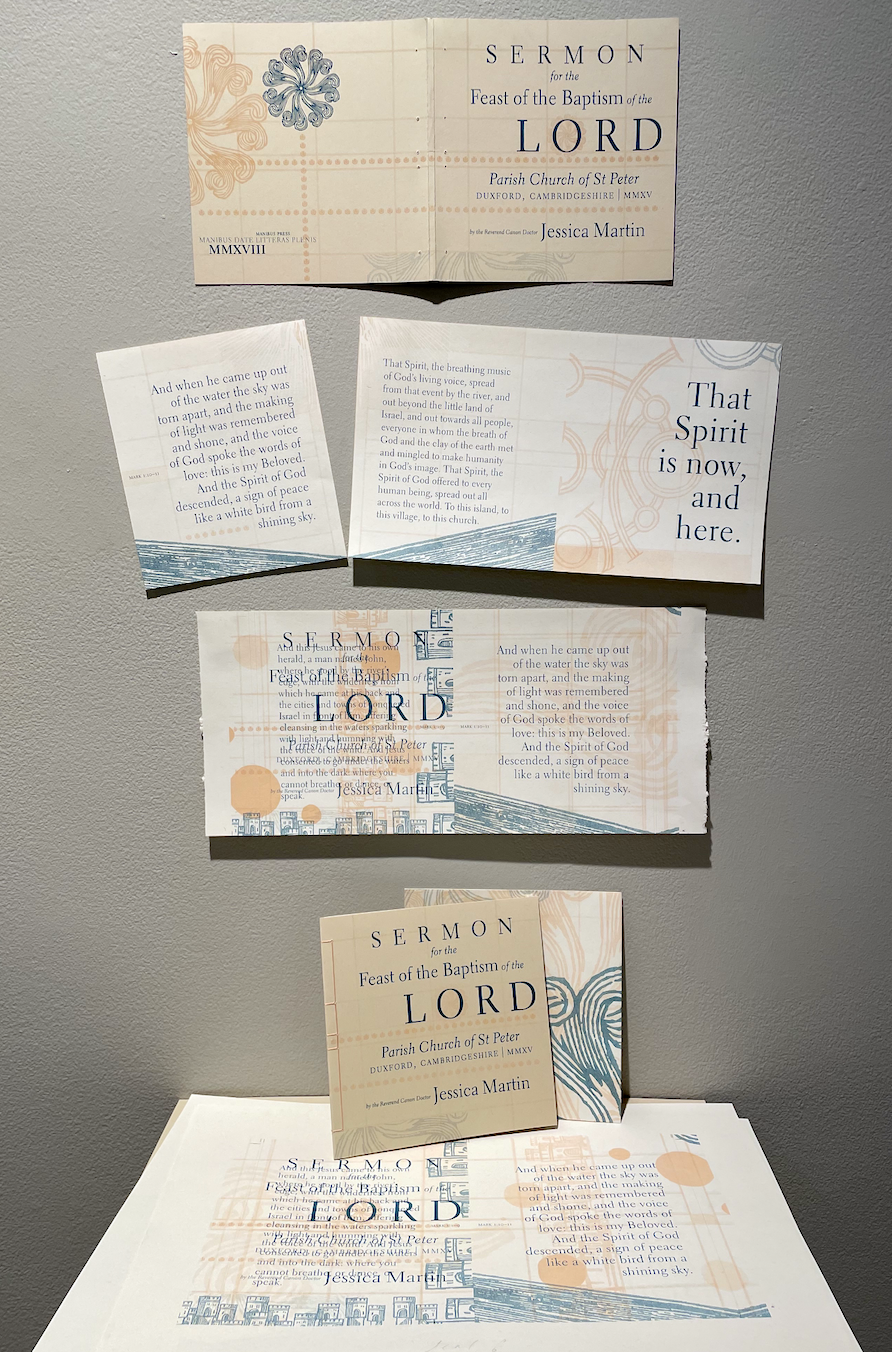

Station #7, Anatomy of the Pamphlet:

Nowadays, the pamphlet is a niche genre; we associate it with primary school education, prescription drugs, and instruction manuals. But from the early fifteenth century to the mid nineteenth, the pamphlets were part of everyday life in the West. Cheap to print, simple to bind, and easy to pass around, the pamphlet was among the principal media for the dissemination of news and views, radical and conservative alike. The objects you see before you represent creative renewals of the pamphlet form assembled by Botts, Gibson, and past participants in the Technotexts seminar. Each of the projects introduces elements of fine press printing and modern design into yesterday’s quotidian media. This station is meant to offer an anatomy lesson that allows you to see how these pieces were built and how their designs evolved. Feel free to interact with the “pamphlet guts” spilled on the table before you.